Introduction and Context

This case study is the first of its kind in Italy, combining qualitative insights and hard data to offer a comprehensive look at the threats faced by environmental journalists. For the first time, an updated statistical analysis of threats against environmental reporters – from 2011 to 2025 – is presented alongside dozens of in-depth interviews.

At the center of this investigation is the story of a journalist who endured three separate waves of online attacks. Her experience allows us to uncover the network behind these digital assaults and examine how such campaigns are orchestrated. But she’s not alone: we also hear from local journalists and freelancers who face daily pressures, from external intimidation to self-censorship and the looming threat of SLAPP lawsuits.

Strikingly, all but one of the journalists we interviewed chose not to report these cases to the national Ordine dei Giornalisti or Union. In this report, we explore why so many episodes go unreported – and what that silence says about the state of press freedom in Italy today.

Context

Italy slipped to 49th place in the World Press Freedom Index compiled by Reporters Without Borders, dropping three positions compared to the previous year. A significant step backwards, placing the country alongside nations like Romania and Mauritania.

The report describes Italy’s situation as “problematic,” highlighting the impact of certain laws promoted by the governing coalition led by Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni. An ironic note: Meloni is officially registered as a journalist.

But it’s not only the increasingly restrictive legal framework that hampers the work of the press. In Italy, trust in the media and the journalistic profession has been declining for decades. This is also reflected in the consistent drop in newspaper sales.

Journalism and journalists are often viewed with suspicion: they spread fake news and protect powerful interests.

And few other topics polarize public opinion as much as the climate crisis and environmental issues.

Landscape and pressures

In our interviews with around twenty journalists covering environmental issues, we found that most of them work as freelancers—a status that leaves them particularly vulnerable. Without the backing of a newsroom, they have fewer institutional safeguards and limited protection against SLAPPs. This professional isolation also makes it more difficult to cope with criticism and external pressure.

Several journalists we interviewed told us they often feel forced to self-censor, fearing their articles might be blocked by editorial boards or could trigger online attacks from groups or individuals opposing certain viewpoints. Many were too afraid to speak openly, which is why we’ve kept their quotes anonymous.

“Sometimes you’re even willing to compromise just to see your piece published,” a freelance colleague told us, asking to remain anonymous.

Moreover, it seems there are certain topics (or companies) that are either off-limits or simply avoided.

“There’s a bit of fear when it comes to confronting big corporations—retaliation is a real concern, and often it just doesn’t seem worth the risk,” explains another young colleague who focuses on environmental investigations.

This phenomenon restricts press freedom and the right to information—at a time when environmental issues are more crucial than ever, especially in a country like Italy.

Serena Giacomin is an atmospheric physicist, climatologist, meteorologist, teacher, and science communicator. She received a flood of insults and even death threats after discussing the chemtrail conspiracy theory on a broadcast alongside an expert. Reflecting on the experience, she told us:

“Right after the program aired, everything went out of control. People who believe in the chemtrail conspiracy said horrible, unspeakable things to me. The comments were violent – some even sexually violent. For several weeks, I was deeply shaken. You start to feel unsafe. I began removing anything from the internet that could reveal where I live. I’ve never been someone who enjoys the spotlight – I’m not used to being filmed or photographed. My presence in public spaces has always been tied strictly to my work. Feeling that exposed was pure torment for me.”

A grey area

In Italy, the journalism profession is regulated by registration with the national professional register. The Ordine dei Giornalisti (Order of Journalists) operates at the regional level, alongside local branches of the national trade union for Italian journalists (FNSI,). While registration with the Order is mandatory to legally practice journalism, union membership remains optional.

Yet, it is precisely the unions that could serve as a primary point of contact for journalists facing threats or pressure. “When I was attacked, I didn’t report it to either the Order or the unions. I don’t have much trust in the first, and I’m not even sure the second has anything in place for us freelancers,” says a journalist who covers environmental issues for some of Italy’s leading publications and who has been targeted by online attacks.

The lack of reports to regional Orders contributes to the creation of a gray area where many incidents go unrecorded. Ossigeno per l’Informazione, an association that has long worked to protect threatened journalists, stated it was unaware of the cases uncovered during this investigation. Likewise, regional Orders and local unions had not received reports of the events we reconstructed, though they expressed their willingness to support the journalists involved.

There is also another factor to consider: in Italy, only those registered with the Order can legally call themselves journalists and access the associated protections. However, the registration process requires specific criteria that not everyone is able to meet.

“I’ve always wanted to register with the Order of Journalists of Puglia, but I’ve never had the chance,” says Luciano Manna, a local reporter who has received multiple threats and has been the target of intimidation, and one of the few journalists that allowed us to disclose his name. His voice reveals a sense of discouragement.

The first Italian statistic

To compile data on attacks against journalists covering environmental issues in Italy, we consulted the only two available databases documenting both physical and online threats. The first, maintained by Ossigeno per l’Informazione, had recorded 2,322 reports as of February 15, 2025. The second, provided by the Media Freedom Rapid Response Mechanism (MFRR), included 757 reports from Italy, with some overlap between the two sources.

Through an extensive data-scraping and cross-referencing process, we isolated cases specifically related to environmental reporting and removed any duplicates. The final total: 114 incidents recorded in Italy between 2011 and 2025.

Most of these threats happened while journalists were investigating environmental crimes or reporting on major energy companies. One striking example dates back to 2017, when a group of reporters was blocked by a security guard while filming near an ENI extraction site—even though they were parked on a public road.

Among the dozens of reports, there are also some particularly striking cases in which the “attacks” come from unexpected sources. One such instance involves climate physicist Antonello Pasini. According to a report collected by the Media Freedom Rapid Response (MFRR, a consortium of six organisations), on August 29, 2024, Pasini’s live commentary during a segment of the national broadcaster RAI’s Tg1 news program was edited in a misleading manner.

Pasini intervened live to state: “The persistent presence of African anticyclones has charged our atmosphere with a large amount of energy.” However, Pasini later claimed on social media that his original comment had been: “The persistent presence of African anticyclones, the result of climate change in the Mediterranean, has charged our atmosphere with a large amount of energy.” The reference to climate change had thus been omitted. Tg1 denied the accusation of censorship, stating that the editorial decision was not politically motivated and reaffirming the program’s ongoing coverage of climate-related issues.

It might seem insignificant, but this episode reveals the nuanced and often subtle pressures that shape environmental journalism in Italy.

More importantly, the 114 documented cases likely fall short of capturing the full scale of the problem. Investigations into individual incidents have uncovered several that were missing entirely from both the Ossigeno and MFRR databases — pointing to a much larger number of threats that go unreported or undocumented. The case we’re about to examine is one such example, part of the broader, largely invisible landscape of attacks that never make it into official records.

Local Journalist at the forefront

The situation becomes even more delicate when journalists work for local outlets, becoming recognizable faces within their communities.

Nuri, a journalist for a local newspaper, spent years investigating a severe case of environmental pollution caused by a factory in one of Northern Italy’s wealthiest cities. Her reporting brought her widespread recognition—but it also came at a great personal cost.

Born and raised in Italy, Nuri has a foreign father, and her name and surname stood out in a wealthy town – a stronghold of Lega Nord – where prosperity coexists with a deeply provincial mindset and a lingering diffidence toward those who don’t quite fit the local mold. For security reasons, we cannot reveal her surname.

“For my articles,” she recounts, “I received a letter at home with racist death threats. What shocked me most was finding out the letter had been delivered by hand: someone had followed me from the newsroom to my house.”

The letter she received contained several racist insults and ended with a disturbing death threat, wishing her to die burned at the stake. In this case too, a report was filed with the police, but no notification was made to the relevant journalistic authorities.

Luciano Manna, on the other hand, works in Puglia, in the far south of Italy, where he reported on a polluting factory and a local community too often neglected and left to face institutional indifference alone. He also investigated illegal fishing off the coast of his hometown – stories that were later picked up by major international media outlets.

His fight for press freedom, carried out in one of the country’s most complex regions, has come at a steep personal cost.

He’s filed dozens of reports with the police for hate messages received on social media, and has faced just as many lawsuits simply for doing his job. In some cases, the threats escalated into death threats and even physical assaults.

“The threats have never influenced my journalistic work, but they’ve had a deep impact on my personal life. They’ve affected my family as well,” he says.

The attacks against Francesca Santolini

Francesca Santolini is a well-known journalist with deep expertise in environmental issues. A frequent guest on television programs, she writes for La Stampa and Repubblica, two of Italy’s leading newspapers.

In April 2024, she published the essay Ecofascisti, which explores how the far right is appropriating ecological themes to justify nationalist and identity-driven political narratives.

Since then, she has found herself at the center of online hate campaigns. The most recent attacks date back to March 2025.

But let’s go in order.

The Chronology of the Attack

On July 30th, Santolini appeared as a guest on a program aired by La7. A short clip from her appearance was extracted and shared hundreds of times across social media, throwing her into a spiral of hate speech: sexist insults, misogyny, death threats, and even threats of rape.

Her fault was supporting a thesis—already backed by numerous academics—that the defense of fossil fuels is, in effect, also a defense of patriarchy.

Establishing the target

Returning to the attacks: just 30 minutes after the program aired, the video was already circulating online. Shortly thereafter, it began spreading rapidly across the web. Between August 3rd and 4th, a well-known blog run by a right-leaning journalist, along with a newspaper from the same political sphere, picked up the story. Within 72 hours, the smear campaign was in full swing.

A threat on Christmas Day

The wave of hate left the journalist deeply shaken—but it was only the beginning of a series of repeated attacks.

In December, a well-known journalist with ties to the political right published a blog post, and a web radio picked up the same clip of Santolini, sharing it again in a mocking tone, ridiculing her views. It didn’t take long for a second wave of insults to erupt – more intense than the first.

“On Christmas Day, I was preparing lunch with my family when I received a message on Instagram from an account created just that day. They wished for me to be raped by black men.”

In January, Francesca Santolini filed a report with the Postal Police in Rome. The account was shut down – likely fake, but it left a lasting impact on the journalist.

“Every time someone starts following me on social media, I fear it’s another troll trying to monitor me. That, too, is a form of intimidation.”

She decided to close her X account.

The third wave: a death threat

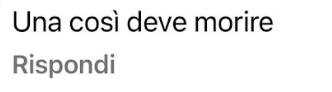

On March 21, 2025, the same out-of-context clip was shared once again on Instagram. The video was accompanied by the phrase: “This woman is out of her mind!” The post sparked a flurry of reactions, generating 1,163 comments, many of which were filled with insults, defamation, and threats—among them, an explicit death threat.

Santolini has filed a formal complaint against the accounts responsible for posting insults, intimidation, and defamatory statements. She has already decided that, should the complaint be dismissed, she will appeal the decision.

Actors and the Ecosystem

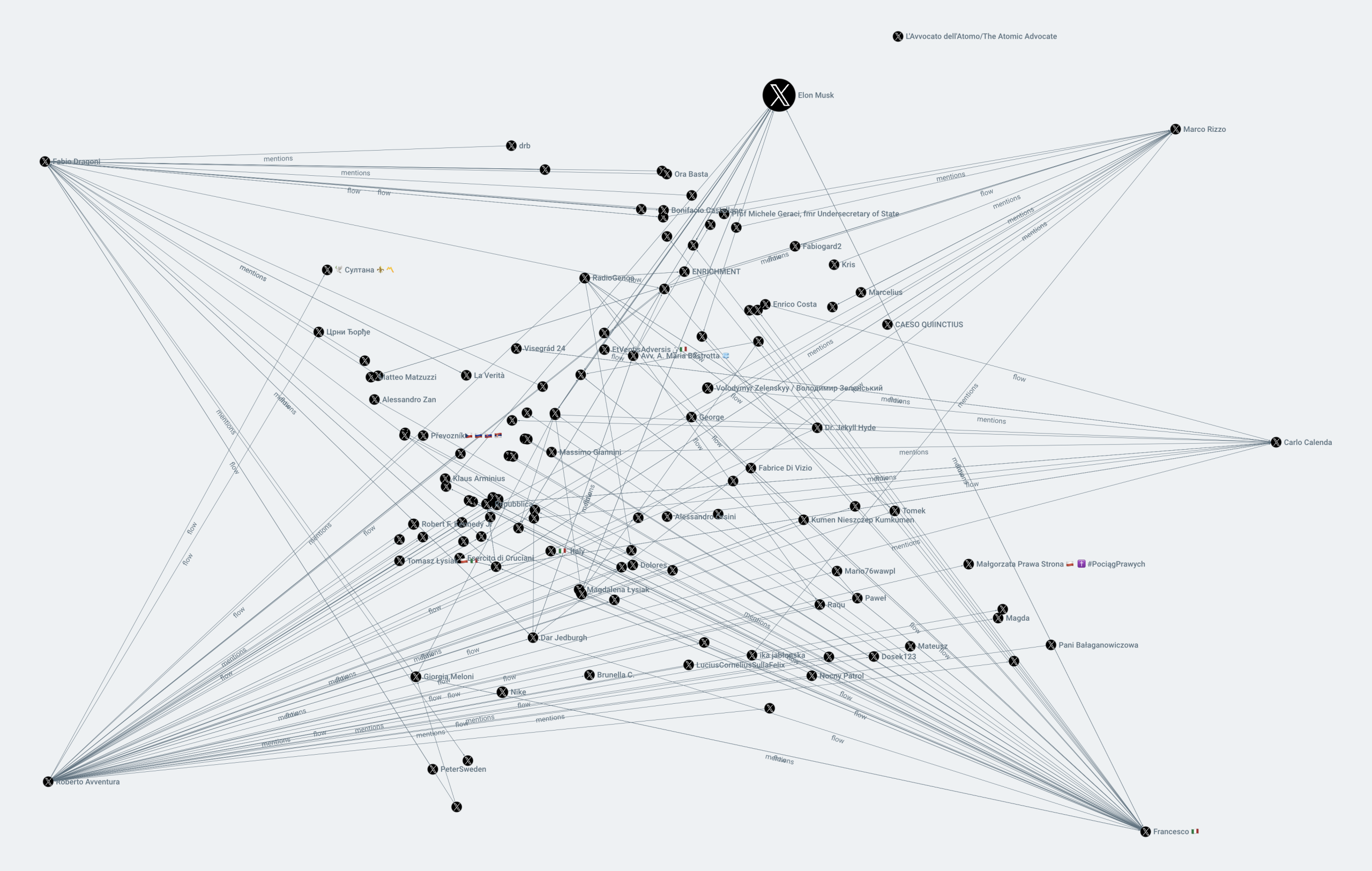

The consecutive waves of hate on social media—especially on X (formerly Twitter)—targeting Francesca Santolini were not triggered by isolated incidents, but rather stem from a well-established network of relationships that initiates discussions and/or attacks targeting individuals or topics that conflict with a shared socio-political worldview.

In the case of Francesca Santolini—particularly during the first two “waves” of attacks—we identified 12 key Twitter/X threads that played a significant role in spreading discrediting and abusive messages against journalist Francesca Santolini.

The first question we sought to answer was whether these accounts were connected and what kind of ecosystem they operated within—that is, which other accounts they followed and the type of discourse circulating within their networks. To investigate this, we used two tools—Gerulata Technologies and Open Measures—both of which include OSINT (Open Source Intelligence) capabilities that enabled us to conduct this analysis.

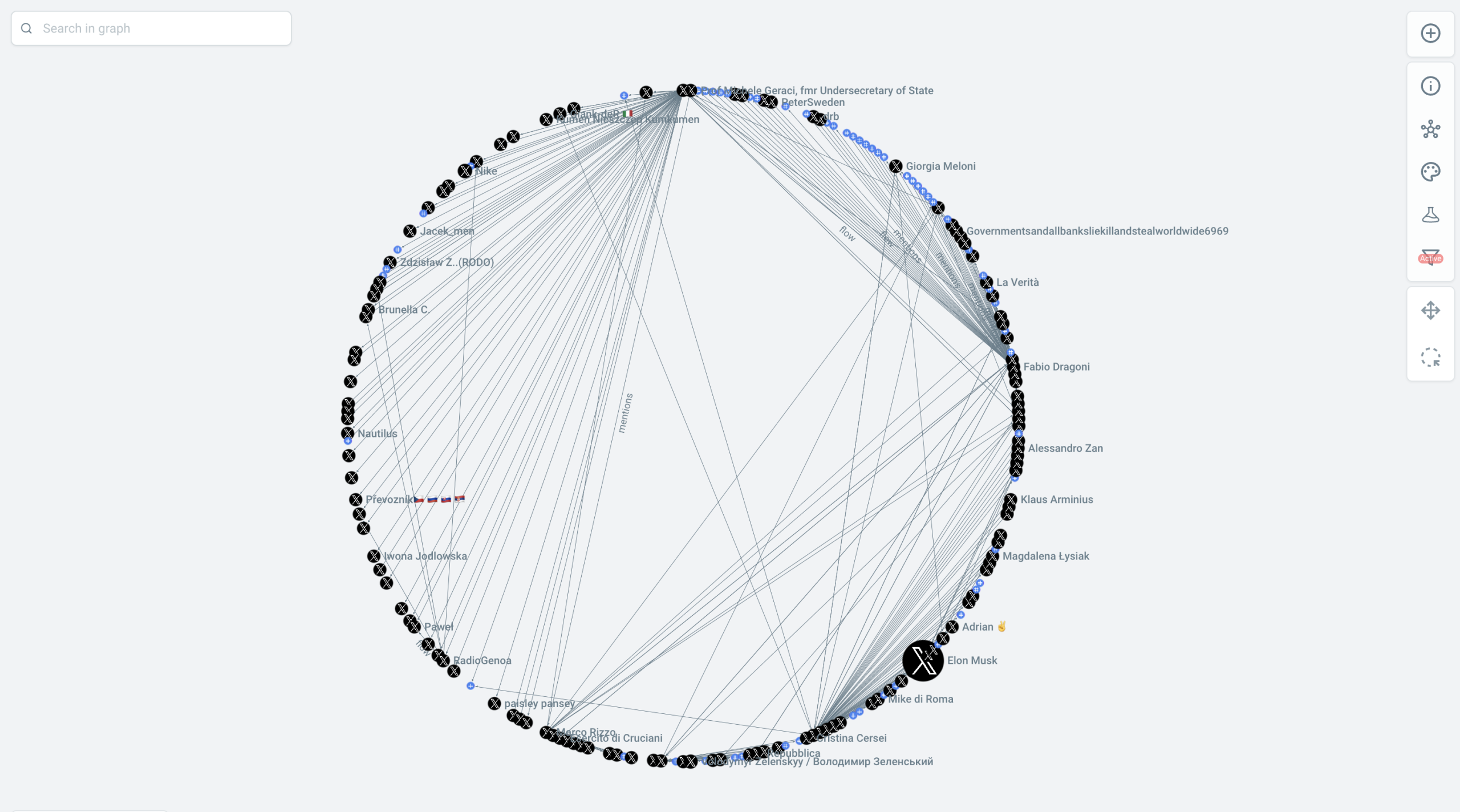

To determine whether there were any relationships among the influential accounts, we carried out a social network analysis (see Graphic 1).

The outer nodes in Graphic 1 represent the accounts influential in disseminating smear campaigns against Santolini. The central nodes represent users who share content from those accounts. Each line connecting the nodes indicates a form of interaction—such as one account mentioning another or sharing content posted by these users.

From this initial analysis, we identified a total of 125 influential accounts within the network and 669 connections among them. It’s important to note that the actual network may be larger; however, our focus remained on accounts directly spreading content targeting Santolini. Additionally, we must consider the limitations imposed by X’s API, which restricts researchers’ access to complete data.

To further explore the ecosystem in which these accounts operate, we expanded our scope to include a narrative analysis. The goal was to understand the types of content being circulated within the network. To that end, we analyzed the most frequently shared hashtags among the key accounts (see Graphic 2).

The most prominent hashtags observed included:

- #TheGreatReplacement: A white supremacist conspiracy theory originating in Europe that portrays immigrants as agents of a plot to replace white Europeans.

- #Ukraine and #Zelensky (with posts criticizing Zelensky for allegedly using civilians as shields to protect the Ukrainian army from Russian attacks)

- #Salvini (associated with anti-immigration rhetoric)

- #Meloni (largely praising content)

- And negative messaging around #Fauci and #Vaccines

This analysis revealed that all the influential accounts in question were interconnected. While we did not find evidence of explicit coordination in spreading the abusive and discrediting messages against Santolini, we did identify consistent interactions among the accounts. These included the promotion of conspiracy theories, anti-European and anti-immigration content, climate change denial, as well as sexist and anti-“woke” narratives.

This type of well-established network typically does not issue overt calls to action urging coordinated attacks against individuals or journalists—particularly when operating on open platforms like X. Instead, the simple act of one account publishing or sharing a message targeting a person (in this case, Santolini) often serves as an implicit signal to others within the network. These users then amplify the message by resharing it, commenting on it, or liking it, prompting X’s algorithm to treat the content as relevant and increasing the likelihood that it will go viral.

Once we established the connection between these accounts and identified the ecosystem in which they operate, we conducted a second type of analysis to identify the pattern of the behaviour among them. These 12 threads were analyzed using the paid software TwCommentExport, which allowed us to extract a list of accounts that posted comments.In total, 2,760 unique accounts participated in the conversations across these threads.

The data we collected is influenced by the changes introduced to Twitter’s API infrastructure following Elon Musk’s acquisition. In particular, the new access limitations may have affected the quantity and type of data available.

While some accounts engaged in multiple threads, the majority-2,448 accounts – contributed only once. Based on our analysis, it is possible that 694 of the 2,760 accounts involved in the attacks were bots.

These profiles – strictly hidden behind pseudonyms – share certain common traits: they support pro-Russian propaganda, hold anti-vaccine views, and exhibit a strongly anti-European stance. It is common to find posts dedicated to recurring figures such as Elon Musk, Donald Trump, and Giorgia Meloni. These names frequently appear in their content, accompanied by positive comments, expressions of admiration, or outright praise, reflecting the ideological alignment of the individuals behind these profiles.

Based on our investigation, we found that the attacks against Francesca Santolini originated from an organized network that selects specific targets and triggers what appears to be, coordinated actions on X and Instagram. However, we have also identified some instances in which this topic or case was also discussed on VKontakte – a social network very popular in Russia – and on Gab, a U.S.-based microblogging platform known for its far-right user base, as well as on numerous Telegram channels. Although these platforms were out of the scope of the current analysis, it is worth mentioning that a more in-depth analysis on these alternatives platforms should be conducted in the future.

Main narratives

🎯 as a mark: emojis and the language of online hate

A recurring element among the analyzed profiles is their peculiar use of emojis. The use of emojis within online hate subcultures is still an underexplored but highly significant phenomenon. These groups – active on platforms like 4chan, Telegram, Reddit, or encrypted channels – use emojis to disguise hateful messages, bypass moderation systems, and construct internal languages that strengthen a sense of belonging.

In our case, we identified the repeated use of the 🎯 emoji, employed as a symbol to identify, mock, target, or “mark” individuals or groups for attack. While the emoji itself does not inherently carry a hostile meaning, it takes on an aggressive connotation within this specific communicative context. The symbolic target 🎯 was used repeatedly in the sharing of the now-famous video clip featuring Francesca Santolini.

Another significant finding from the analysis concerns the technical proficiency of the attackers. One of the most widely shared videos is, in fact, the result of editing—a technique that requires a certain familiarity with digital tools. This suggests that the attacks may be a coordinated effort behind the scenes that guides and facilitates their dissemination.

Main narratives targeting Santolini

media is spreading fake news

The insults directed at Francesca Santolini all shared a common thread: the idea that the media spreads fake news and that journalists are subservient to so-called “powerful interests.” A significant example of this can be found in a comment posted under the YouTube video that re-shares the now-famous clip from the television program aired on La7.

In the message, the word “scientifica” (scientific) is written with the letter S replaced by the dollar sign and the letter E by the euro symbol—an act of mockery meant to highlight how journalists—especially those writing about scientific topics—are allegedly in the service of money and higher interests.

This attitude reflects the echo of the anti-vax movements, particularly entrenched in Italy, which have questioned all forms of scientific knowledge.

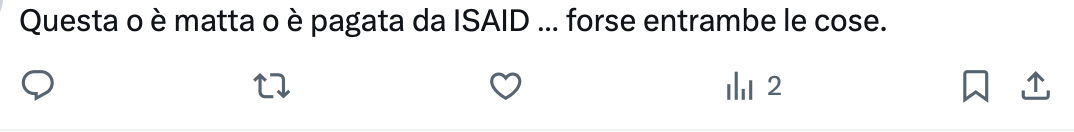

Some messages even mention USAID (which is misspelled as “ISIAD”), the United States government agency responsible for international development, implying unfounded connections.

Another comments accuses the journalist of serving foreign interests and includes an explicitly fascist statement: “she should be arrested and re-educated.'”

Misogynistic attack

As often happens when insults are directed at a woman, the focus quickly shifts from the professional sphere to the personal and sexual. This is evident in a comment posted on X: no explicit language, but a clearly offensive tone. It alludes to the idea that the journalist should “stay in the kitchen and stir the sauce,” implying that a woman should not publicly express herself, have strong opinions, or discuss serious issues. This type of attack seeks to undermine the legitimacy of women’s presence in the public space, especially when it comes to journalism and debate. Countless messages targeted her, using sexist insults.

Other messages, such as the one received on Instagram and included in the report we published, go beyond verbal intimidation: they are outright rape threats, with openly racist undertones. In this case, the language leaves no room for interpretation and takes on the characteristics of a targeted, violent assault, with a clear intent to intimidate. This attitude closely resembles fascist tactics and is not just limited to a single incident, but fits into a broader, more troubling pattern of online violence.

In another message, a user expresses the hope that “the white male will take control.”

And then: “So go have fun with the black patriarchy.”

Some threatening messages contain explicit ableist slurs, referencing Law 104, which in Italy protects people with disabilities. In this context, disability is openly used as an insult.

Conclusions

This report is just a starting point: a call to open a broader conversation in Italy about a largely overlooked issue: the threats and online hate campaigns targeting journalists, particularly those reporting on the climate crisis.

While this investigation has focused on a specific group, it raises a much larger question: how many similar cases go unreported? How many coordinated attacks slip through the cracks, unnoticed and undocumented?

There are two key goals at the heart of this work. First, to begin building a support network for freelance journalists who often face these threats alone, so they know there are organizations ready to stand by them. Second, to spark public debate and raise awareness about the growing wave of online hate, because silence only enables it to spread and grow.

An important note

In Italy, even in the face of serious online threats like these we collected, it is not permitted to publish the names of the social media accounts behind them — not even if the profiles are clearly fake. This is due to strict privacy laws (EU Regulation 2016/679 and the Italian Privacy Code) and the rules set by the Journalists’ Code of Ethics, which require respect for personal dignity, identity, and confidentiality, even in digital spaces.

Publishing a name — even just a fake username — without a court’s official confirmation may be considered a violation of privacy or even defamation, unless there is a clear and overriding public interest.

While privacy protection is absolutely essential, Italy is, in practice, the only country involved in this investigation that cannot fully disclose the data collected — not even when the death threats come from anonymous accounts.

Disclaimer:

The sole responsibility for any content supported by IPI lies with the author(s) and it may not necessarily reflect the positions of the IPI and EMIF and the Fund Partners, the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation and the European University Institute.