Introduction

On April 6, 2021, journalist Franziska Tschinderle fired off an email from the editorial offices of her magazine Profil in Vienna’s 19th district to Brussels. The recipients? MEPs from Hungary’s ruling party, Fidesz. Tschinderle tossed them three seemingly “routine” questions. Little did she know that, starting the next day, she would become the target of a relentless assault in the prime time news slot of Hungary’s state TV channel, M1. They plastered her photo, aired her name, and, for five consecutive evenings, launched attacks without fair warning or a chance for her to respond. “They went all out to defame me, painting me as naive and ludicrous as possible,” Tschinderle, reflecting on the ordeal, remarked.

Austria’s ÖVP Foreign Minister, Alexander Schallenberg, stepped in, expressing strong objection.

Attacks on journalists under the Fidesz government’s reign are unfortunately not uncommon in Hungary. Over the thirteen years of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s leadership, he has substantially tightened his grip on the media landscape, both public and private. However, the Tschinderle incident stands out, even in the context of Hungary’s standards. Tschinderle, musing on the surreal situation, noted that in other countries, the idea of a foreign journalist’s inquiry to a ruling party becoming the centerpiece of a state news program is “unfathomable”. “Yet, it occurred in Hungary. The pressing question emerges: Why did they report this? How independent are they, truly? Who crafts such a report?”, Tschinderle said.

Interviews with former employees of Hungary’s state media, academics, activists, politicians and internal documents that we had access to, show how a conglomerate of private and state media has formed in Hungary, for which it is completely natural to work hand in hand with the Fidesz government to discredit critical journalists and independent news organisations.

Political landscape

Assault on Independent Media Since 2010

Ever since Orbán ascended to power in 2010, his relentless efforts to tighten his grip on the media have unfolded on dual fronts. The public media underwent expansion and alignment, while their private counterparts were subjected to defamation, relentless pressure, and strategic acquisitions by Orbán’s loyalists. Fidesz’s narrative now permeates virtually all communication channels in Hungary. The pivotal change occurred in 2010 with a new media law that consolidated public broadcasters under a single entity, effectively erasing internal plurality. Control over both public broadcasting and the media oversight authority fell into the hands of Fidesz appointees, solidifying their sway over private media.

Whistleblowers allege that Antal Rogán, head of the prime minister’s cabinet office, plays a central role in steering and overseeing media narratives. Referred to by the opposition as Orbán’s propaganda minister, reports claim that Rogán allocates advertising contracts to media outlets acquired by Fidesz-affiliated oligarchs, subsequently handed over to the Fidesz-controlled “Central European Press and Media Foundation” (KESMA). These publications now report daily on similar topics, often with uncanny similarity, and increasingly echo themes of Russian propaganda. Rogán stands as a prominent figure in Hungary’s Kremlin connection.

The media landscape in Hungary is now starkly divided: traditional media, encompassing radio, television, newspapers, and magazines, align with the government’s stance and fall under the influence of Fidesz-associated investors. Independent, critical voices predominantly exist online, yet their reach is notably limited, especially in rural areas.

These observations find resonance in the Media Pluralism Monitor 2023, a project by the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom at the European University Institute. The country report on Hungary underscores: “Hungarian public service media is financially dependent on the governing majority in Parliament, is controlled by political interests and is seen as extremely biased in its reporting” Additionally, the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom notes Hungary’s deployment of Pegasus spying software against journalists and media proprietors.

In reshaping Hungary’s media landscape, financial power and the acquisition of newspapers, often by Fidesz-affiliated investors, have proven more influential than state repression. Formerly critical outlets, like Origo, which exposed corruption within Orbán’s circle, were acquired by Fidesz-aligned New Wave Media in 2015 after Hungarian Telekom, a subsidiary of the German company Telekom, sold it. Deutsche Telekom, in return, secured mobile frequencies and a multibillion-dollar government contract to expand its broadband network. The new owner of Origo, a close associate of Orbán, swiftly aligned it with the government’s narrative.

Similar scenarios unfolded with various media entities. In 2018, the conservative Magyar Nemzet, the last national daily not under government control, shuttered. Subsequently, in 2019, a pro-government daily assumed the mantle of Magyar Nemzet.

The Rule of Law Report 2023 from the EU Commission, submitted in July, underscores that the channeling of substantial state resources into pro-government media obstructs a level playing field in Hungary’s media landscape. The EU Commission also critiques Hungary’s media law design and the independence of its overseeing authority, the Media Council. The 2023 Rule of Law Report emphasizes the Media Council’s composition, entirely appointed by the ruling party-controlled parliament, leading to decisions that hinder media freedom. A glaring instance is the refusal to renew the broadcasting license of the independent radio station Klubrádió, resulting in its forced closure. Consequently, on July 15, 2022, the Commission initiated infringement proceedings, deciding to take Hungary to the Court of Justice.

Establishment of autocratic media control

Orbán’s media law has garnered global criticism, triggering a significant shift in the media landscape. Central to this transformation is the Media Services and Support Trust Fund (Médiaszolgáltatás-támogató és Vagyonkezelő Alap, MTVA), a kind of a central editorial hub for state media. Since 2018, Dániel Papp, an ex-functionary of the far-right Jobbik party, has led MTVA with an annual budget exceeding 250 million euros. The agency now produces and disseminates all pro-government news to various platforms, consolidating control over five TV channels, four radio stations, and a news agency that provides news to other media outlets for free. As a result, the private Hungarian news agency, critical of the government, went bankrupt, leaving MTVA as the sole source of Hungarian language news.

In December 2010, deputies from the Fidesz and Christian Democratic People’s Party alliance passed a law establishing the Media Services and Support Trust Fund (MTVA). This law merged the state media outlets—Hungarian Radio, Hungarian Television, Duna Television, and the Hungarian News Agency—under MTVA’s management. The merger granted the Hungarian News Agency (MTI) exclusive rights to produce programs for Hungarian Radio, Hungarian Television, and Duna Television (see text of law in English). Prior to this, these outlets had independently produced their own programs.

Administered by the State Media Council (Médiatanács) of the National Media and Infocommunications Authority (Nemzeti Média- és Hírközlési Hatóság), MTVA’s director is appointed by the council. The Közszolgálati Közalapítvány (Public Service Foundation), an eight-member board of trustees, appoints directors for Hungarian Radio, Hungarian Television, Duna Television, and MTI. The foundation includes appointees from both the ruling coalition and the opposition in the National Assembly, as well as members appointed by the Media Council.

While the Orbán government argues that the merger has enhanced efficiency and reduced operating costs, critics contend that it has transformed the organization into a propaganda tool for the government. The managing director of the Hungarian News Agency, Csaba Belénessy, expressed in December 2010 that “A journalist in the public service cannot be the enemy of the government, he or she cannot question the authority of the freely elected cabinet. It cannot be that we take a position and then turn against the employer.”

Currently subordinate to the Hungarian Media Authority, MTVA is overseen by Antal Rogán, head of Orbán’s cabinet office, who also coordinates civilian intelligence services. A 2019 survey by the NGO Mérték revealed that government media constituted 78 percent of Hungarian media sector revenues, serving as a potent tool to target perceived enemies of the Fidesz project.

In February 2023, during an investigation into the rule of law, a delegation from the EU Commission visited Budapest. MTVA head Dániel Papp defended the organization, citing “guarantees of balance and impartiality” in the MTVA Code of Ethics and the Media Act. He accused opposition parties of attempting to politicize public service media with false claims. “A basic rule for the work of Hungarian public service media is that politics must not influence the production of content”, Papp claimed. The Tschinderle case, however, casts doubt on these assurances, illustrating the treatment of Orbán opponents and unpopular journalists through defamation and intimidation.

In 2017, the pro-government portal 888 published a list of eight correspondents as “Soros’ foreign propagandists,” accusing them of discrediting Hungary internationally. Independent journalists suspect the government maintains lists of critical journalists, denying them interviews and access to press conferences. Conversely, broadcasters exhibit loyalty to the government, as revealed in an email instructing an MTVA reporter on specific parts of Viktor Orbán’s speech to highlight.

Radio Free Europe uncovered instructions at MTVA to report in a pro-government manner before the 2019 EU parliamentary election. Secretly recorded audio from a March 2019 meeting indicated that the opposition was not supported within the institution, with dissenters encouraged to resign, as voiced by Balázs Bende, the head of the foreign department responsible for reports on Franziska Tschinderle, whom taz interview for this report.

Attempts to form a faction of far-right parties in the EU

In her email to the Fidesz deputies, Tschinderle inquired about a recent meeting where Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán had convened with then-Italian Interior Minister Matteo Salvini and Poland’s Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki in Budapest. The trio proclaimed the establishment of a new alliance of parties, envisioning a “rebirth of Europe based on Christian values,” as articulated by Orbán.

Tschinderle’s email delved into the purpose of this alliance, questioning why notable parties such as FPÖ, AfD, or Marine Le Pen’s French Rassemblement National were absent from the gathering. She sought answers to the failures of past attempts to forge such alliances, often hindered by political disparities. A critical concern was how to prevent a split this time, addressing one of the right’s significant strategic challenges in Europe. Previous endeavors, predating the 2019 EU elections, aimed at creating a joint list with a shared election program and a potential top candidate faltered due to irreconcilable differences on economic policy, anti-Semitism, and notably, the issue of Russia. The post-2019 “Identity and Democracy” group, formed after these elections, ranks only as the fifth-largest in the EU Parliament until the 2024 election, despite significant support for extreme right-wing parties across many countries.

References to George Soros in Hungarian government communication

The restructuring of Hungary’s media landscape and the discrediting of dissenting journalists, is contextualized within a broader right-wing culture war. This ideological struggle positions itself as a defense of the nation against perceived threats from “globalists,” the “woke” movement, and liberals. The free press finds itself squarely within these contested groups, facing fierce opposition, exemplified by the ordeal of Franziska Tschinderle.

Repeatedly, independent media, liberal NGOs, and institutions are linked to one individual: George Soros. The billionaire philanthropist, a survivor of the Holocaust in Hungary who later migrated to the United States, is the target of animosity from Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and his government. Soros, through his Open Society Foundation, advocates globally for democracy, liberalism, and human rights.

Orbán and his government perceive Soros as part of a conspiracy against Hungary, fearing a scheme to dismantle nation-states, influence migration policies, and harbor various other ideas about Soros’s clandestine influence. The anti-Soros campaign commenced in 2013 and reached its zenith after the 2015 during the refugee crisis.

The accusations against Soros echo classic anti-Semitic narratives, portraying him with stereotypes of homelessness, secrecy, world power ambitions, and an alleged conflict between productive work and speculative malevolence. In a 2018 speech, Orbán said: “We are fighting an enemy that is different from us. Not open but hidden, not straightforward but cunning, not honorable but dishonorable, not national but international, who doesn’t believe in labor but speculates with money, who has no homeland of his own but acts as if he owns the whole world.”

While Jewish life in Budapest is vibrant, and many Jews report feeling secure in Hungary, the government exploits anti-Semitic stereotypes for its policies, influencing public sentiment. The enactment of a “Stop Soros Law,” targeting NGOs advocating for refugee and migrant rights, marked a decisive move by Hungary’s government, leading to the expulsion of the Central European University (CEU) from Budapest, a institution co-founded by Soros.

Opposition deputy Marton Tompos of the Momentum party sees the campaign against the CEU as an example of Fidesz’s sophisticated public relations strategy. In this campaign, the term “Soros University” wasn’t chosen arbitrarily; instead, party strategists conducted surveys to determine which name would provoke the strongest reaction, and they found it in Soros, Tompos stated in an interview for this report.

Chronology of the attacks on Franziska Tschinderle

Tschinderle’s e-mail to Fidesz

This is the original text of the press inquiry Tschinderle sent to the Fidesz press office at the EU Parliament in Brussels on April 6, 2021:

My name is Franziska Tschinderle, a journalist working for the Austrian weekly ‘Profil’. In our next issue we will draw attention to a possible new right wing European alliance that has been announced End of March by Viktor Orbán, Matteo Salvini and Morawiecki in Budapest.

We are talking to MPs from different countries and parties, such as the Austrian FPÖ, the French Rassemblement National, the Italian League etc. We would be interested in getting to know the Hungarian view on this project.

1) When Orbán, Salvini and Morawiecki joined forces in Budapest and announced the possible creation of a new alliance: why was no one from the French Rassemblement National or the Austrian FPÖ present at this historic meeting?

2) What is the goal of the alliance and who considers joining it?

3) The creation of an Eurosceptic-coalition isn’t a new phenomena and goes back to the 1980s. It failed several times, because of diverging views on topics such as Turkey and Russia, but also anti-Semitic attacks. How to avoid a split this time?”

The disinformation campaign on Hungary’s Public Broadcaster against Tschinderle

MTVA owns the M1 channel, airing the country’s pivotal news program, “Híradó,” daily at 7:30 p.m. On April 7, during minute 35 of the broadcast, the “Híradó” presenter discussed an “Austrian liberal journalist” who supposedly posed “provocative questions” to Fidesz deputies. Accompanied by her photo and a screenshot of her email, the segment contends that Tschinderle’s questions were “ridiculous” and “amateurish,” masking “preconceived, biased statements.” Allegedly, her aim was to preemptively attack the emerging European Christian Democratic alliance, marking an “unprecedented attack by the liberal European press.” This narrative persists for four minutes before transitioning to soccer.

Until April 10, Tschinderle faces continued attacks, prominently featuring her name and photo in five consecutive issues of “Híradó.” The accusations remain consistent:

Broadcast 08.04.2021

Broadcast 09.04.2021

Broadcast 09.04.2021

Broadcast 11.04.2021

From April 8, significant state-affiliated media outlets amplify the discourse, including online portals Origo, the Mandiner Group and Magyar Nemzet. They assert that Tschinderle sought quick fame by portraying Hungary as a Nazi dictatorship.

Following Threats

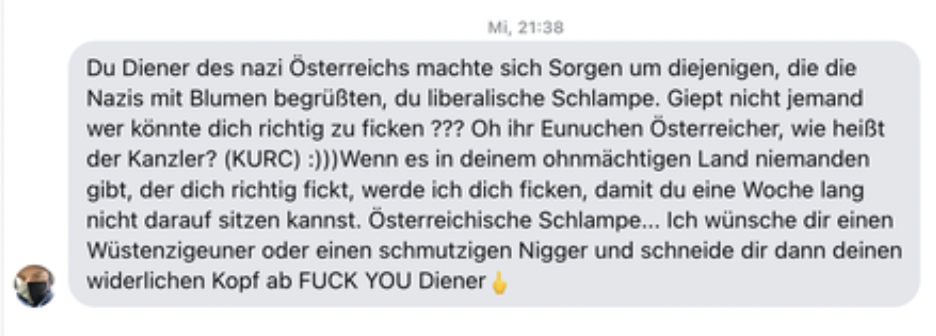

After the televised reports, Tschinderle received numerous messages expressing solidarity from people in Hungary, thanking her for her work. Amidst the supportive messages, a few persist with the M1 propaganda. One hate message, in particular, stands out; received via Facebook on the evening of April 28, it includes threats of multiple rapes and the grotesque promise to “cut off her disgusting head.”

The sender, located in Germany but originally from Hungary, writes under his real name. The editorial team reports him on suspicion of threats. Although the whole team initiates legal action, Tschinderle’s personal data, including her home address, remains protected. Nonetheless, she opts to block the information, marking the first time she secures the suppression of her address.

Within a few months, the investigating public prosecutor’s office identifies the message’s author, leading to a €1,200 fine by the competent court. Tschinderle notes the rarity of hate messages being reported, and the successful trial stands as an exceptional outcome.

International criticism

Amidst the controversy, Tschinderle received solidarity from various quarters, including the Hungarian opposition party Momentum Mozgalom and Reporters Without Borders (RSF). RSF condemned the attempt to stifle critical journalism through state television, deeming it unacceptable. However, M1 manipulated the statement, quoting it the next day to argue that liberal media and NGOs are colluding to attack Hungary’s media in defense of Tschinderle.

The SPÖ and the Greens also condemned Hungarian state TV’s actions, referencing former Austrian Chancellor Sebastian Kurz’s past cooperation with Fidesz at the EU level. They characterize the tactics as reflective of a party striving to retain Kurz within its own EPP group at all costs.

Diplomacy

The vilification of journalist Tschinderle sparked diplomatic tensions between Austria and Hungary. Two days after the initial incident, the Austrian Foreign Ministry tweeted, “Asking critical questions is a core task of the media. M1’s handling of Tschinderle is therefore indefensible.”( Foreign Minister Alexander Schallenberg promptly phoneed Hungarian Foreign Minister Péter Szijjártó. The Austrian ambassador to Hungary, Alexander Grubmayr, is set to convey this position clearly.

In the April 7 phone call, Schallenberg vehemently expressed his “clear rejection” about the attack deeming the reporting “completely unacceptable”. He underscored the core task of journalists to ask critical questions. Despite these efforts, Szijjártó dismissed the criticism on Facebook, decrying “hypocrisy” and claiming that a liberal journalist can spread fake news about a country under the guise of press freedom, but criticism from another journalist is labeled an attack on press freedom.

The role of Fidesz

Given the evidence, we could infer that the Fidesz group in the EU Parliament played a role in Tschinderle’s questions reaching MTVA. The parliamentary group maintains silence on the issue, with neither Paulik, a group member, nor Tamás Deutsch responding to inquiries this team sent.

Balázs Bende, the primary author of the reports on Franziska Tschinderle, had a longstanding career in public television, serving as the head of MTVA’s foreign affairs department for over 20 years. Bende, who had his own magazine and commented on world events, abruptly resigned in 2022, officially citing health reasons. Since his retirement, Bende has remained secluded, declining all interview requests. However, the team of investigative journalists at taz, were able to interview him in-person to address the TV reports against Tschinderle on prime time state television. In the interview, he claimed not to be the author of the initial contribution. He had no prior knowledge of Franziska Tschinderle or the magazine Profil, where she works.

According to Bende, Tschinderle’s questions were not aimed at seeking information but rather at making a “political statement” about Hungary’s government having close ties to far-right groups. He criticized her questions as “not fair,” contending that they portrayed Hungarian voters as lacking understanding of democracy and the world: “They [the questions] gave the impression that Hungarian voters understood nothing about democracy, nothing about the world. They had cast their vote rashly and the result was an oppressive, far-right, xenophobic government breathing down people’s necks and dragging them through the mud. It was an insult toward a Hungarian.”

Bende, while not regretting producing the TV reports on Tschinderle, said: “I think it was an episode in the history of European journalism that wasn’t necessary.” He also noted facing criticism from international media afterward.

Regarding how Tschinderle’s email ended up with him, Bende recalled that the government sent the information to the media, likely through “a press officer or something”. “Everything”, he said, “arrived via email”, first in English and later in Hungarian.

Márton Tompos, who has faced targeted attacks himself, interpreted the media attack on Tschinderle as part of disinformation by Fidesz. He suggested that the story aimed to drown out important news with a background noise of other stories, creating emotional narratives that benefit the party.

Tompos highlights Fidesz’s sophisticated public relations system, assuming that critical inquiries to a Fidesz association are promptly escalated. For Tompos, the attack on Tschinderle serves the purpose of determining the discourse and unsettling people with irrelevant news, ultimately favoring Fidesz.

Tompos explained the quite subtle mechanisms in everyday media life with an example of his own: “If I criticize Viktor Orbán, you don’t directly call me a liar on TV but the whole report begins with a statement by Orbán that the criticism is just an attempt to discredit him. Then follows the opinion of some so-called expert who supports him, and only then is the original accusation even mentioned.”

Fidesz, he said, “wants to determine the discourse, that is, what is talked about. With irrelevant news, people would be unsettled. This benefited the strongest and loudest voice – that is, Fidesz.”

Viktória Serdült, working for the online portal of Hungary’s last independent weekly newspaper, Heti Világgazdaság (hvg), is well-acquainted with Fidesz’s methods of intimidating journalists.

Franziska Tschinderle and Serdült have worked together several times. Serdült is well acquainted with the Fidesz government’s methods of intimidating critical journalists and has been affected by them herself. However, the campaign against Tschinderle was unexpected: “This was absurd. I mean, we are used to propaganda reports, and they are used to shaming journalists,but this one was completely out of the blue.” Up to that point, the Austrian journalist was virtually unknown in Hungary.

As to why exactly she was attacked on M1, Serdült can only speculate: “We really have no idea why Franziska was targeted. My only guess would be her long article on Viktor Orbán. They don’t really like these big articles on the big leader.” In May 2020, Tschinderle published a portrait of the Hungarian prime minister titled “Viktor, the Mighty“.

It’s about Orbán’s transformation from a “cosmopolitan liberal to right-wing conservative.” Hvg published a translated version of the text. The day after the first TV report aired on M1, Franziska Tschinderle told hvg that she would not stop reporting on the decline of democracy in her neighboring country. The hvg article was written by Viktoria Serdült. A screenshot of the article, on which Serdült’s author profile can also be seen, landed on M1 the following day – as proof that the “liberal media” were commenting without knowledge of the actual facts and were deliberately misunderstanding the case.

By publishing Franziska Tschinderle’s press inquiry, M1 had not wanted to draw attention to political problems, but only to problems within the press.

The consequences

William Horsley, the director of the Center for Media Freedom at the University of Sheffield and a board member of the Association of European Journalists AEJ, has officially lodged a complaint with the Council of Europe regarding the incident. According to Horsley, “The derogatory comments and insults against Tschinderle violated the standards of impartiality and tolerance common in Europe for public broadcasters.” The Hungarian government is obligated to respond to the Council of Europe, but as of now, no comments have been provided.

In February 2023, during an investigation into the rule of law in Budapest by a delegation from the EU Commission, MTVA head Dániel Papp highlighted “guarantees of balance and impartiality” found in the MTVA code of ethics, media law, and the code of ethics of public broadcasting. Papp accused opposition parties of wrongly attempting to “drag the public service media onto the political stage” through “lies.” He asserted that statistical evidence proved that public service media had extended opportunities to all parliamentary parties for reporting, opportunities which the parties had allegedly not utilized. Papp emphasized that a fundamental rule for the work of Hungarian public media is the prohibition of political influence on content production.

Simultaneously, the EU Commission’s 2023 Rule of Law Report cited numerous deficiencies concerning media and press freedom in Hungary. The report referenced the Media Pluralism Monitor for 2023, stating, “Hungarian public media are financially dependent on the government majority in parliament, are controlled by political interests, and are considered extremely biased in their reporting.”

Several European embassies, along with the U.S. Embassy in Budapest, have reached out to Tschinderle. At the behest of the U.S. Embassy, she was invited to an internal conference of these embassies, where she reiterated her case to the ambassadors. In 2017, the then-head of the U.S. Embassy expressed concerns about eroding press freedom in Hungary, noting that media outlets closely affiliated with the government had published the names of individual journalists characterized as threats to the country.