Context

The morning of October 29, 2024, will be etched into Spain’s collective memory—especially that of the Valencians. By mid-morning, images were already circulating of torrential rains that would soon become a national tragedy.

The widespread flooding was caused by a DANA (Depresión Aislada en Niveles Altos), a weather phenomenon specific to Spain which is characterized by a low-pressure system that becomes isolated and results in the release of extremely large amounts of precipitation. In 2024, several areas experienced more than a year’s worth of rainfall in a matter of hours, an event likely exacerbated by climate change.

According to the latest government data, 236 people lost their lives in the resulting flooding, making it one of the deadliest natural disasters in Spanish history. The vast majority of casualties were in the Valencian Community (228), but also in Castilla-La Mancha (7) and Andalusia (1). The floods impacted 78 municipalities, mostly small towns like Paiporta, Massanassa, Sedaví, Picanya, and Alfafar, among many others.

Ferran Garrido, an RTVE journalist and Valencian native, described the human and material toll he witnessed upon arriving at the scene of the flooding:

“Imagine what this means: cities destroyed, completely destroyed. […] All their ground floors had been emptied, and practically all belongings, all properties, all cars were piled up in the middle of the street. […] On some streets, we still found mud above knee level.”

In this context of devastation, the attacks against journalists like Ferran Garrido were not isolated incidents. Several reporters from RTVE, La Sexta, Telecinco, and other outlets were physically assaulted, interrupted during live broadcasts, and targeted in online smear campaigns.

As Oscar Nieto, President of the RTVE News Council points out, these attacks took place in a highly polarized political context:

“The attacks against RTVE journalists have reached very high levels. Shouts of ‘Spanish Television manipulates’ and ‘tell the truth’ have become common during any public coverage, with particular ferocity during protests, demonstrations, and political events.”

In fact, the severity of the attacks prompted the News Council to issue a public statement calling for an end to the intimidation of journalists. In an interview with IPI, Nieto described what some journalists experienced while covering the disaster on-site:

“The statement was a call to society and all political parties to defend freedom of information and the safety of workers. [During the DANA], we became even more visible because we arrived with a television camera, a spotlight, and a light projector to illuminate the reporter in areas darkened by flood damage. And, of course, groups would immediately organize to harass the reporters.”

Clara Jiménez Cruz, CEO of Fundación Maldita and an expert in disinformation, contextualized the situation in an interview:

“Tensions were extremely high—and understandably so. Desperation was palpable, fueled by months of rhetoric accusing RTVE of ‘manipulating’ and ‘serving the socialist government of Pedro Sánchez.’ All this in a climate of increasing political polarization and the rise of ultranationalist movements.”

This combination is key to understanding what happened. As Ferran Garrido himself recounts:

“I hadn’t seen people this devastated in a long time. They were truly suffering. Especially in those first moments, when everything was extremely difficult. […] Those were moments of deep pain, intense stress, profound anxiety. Many people still didn’t know where their family members were.”

Garrido himself was, in a way, also a victim of the catastrophe:

“Yes, yes. My town looked like a truck had run over it. […] In some places, the water reached 1.85 meters.”

Despite his personal loss, he chose to return as a reporter—not a victim:

“I volunteered to go from Madrid and report on what was happening in my homeland. But obviously, the people who attack us have no idea who you are. They know nothing about your life.”

This case study defines “attack” as both physical intimidation experienced by journalists on the ground and online comments or campaigns inciting further harassment. While there is no conclusive evidence of a coordinated effort among aggressors, three key factors created an especially hostile environment for the press:

1. Collective Grief

Thousands lost everything—family members, homes, possessions—and the media coverage became an immediate outlet for their frustration.

2. Institutional Miscoordination

The perceived lack of coordination between the regional Valencian Community government and the central Spanish government during the early hours of the disaster drew sharp criticism. The public’s sense of abandonment only fueled their resentment.

3. Pollution of the information ecosystem

Political influencers and conspiracy content creators disseminated edited videos of incidents involving journalists, often accompanied by messages questioning their impartiality and delegitimizing their work. These posts not only went viral but were amplified by large-audience accounts.

This volatile mix, as demonstrated by the attacks on RTVE journalists, made news coverage a risky endeavor—both physically and symbolically. The systematic discrediting of public media and the erosion of trust in journalism were as significant as the assaults themselves.

Chronology of the Attacks Against Journalists

The First Incident: Manipulation and Disinformation on Social Media

On the night of November 4, 2024, journalists from the Spanish public broadcaster were the target of a smear campaign on social media that laid the groundwork for subsequent attacks. The campaign aimed to discredit the coverage and journalistic rigor of Spain’s Public Broadcaster (RTVE) during the events surrounding the visit of the country’s highest authorities and institutions to the DANA-affected areas.

That day, King Felipe VI, accompanied by Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez and Carlos Mazón, President of the Generalitat Valenciana, visited one of the disaster-struck zones to show support for the victims. However, the visit was anything but peaceful—locals greeted the officials with shouts, boos and even mud-throwing.

The most tense moment came when the King, moving his umbrella to greet people, was splashed with mud—a viral image. Sánchez and Mazón also faced hostility, including insults; the Prime Minister even chose to leave before the others.

Garrido explains that a video appeared on the Internet that very night accusing Spanish Television of manipulation:

“That very night, a video appears online saying that Spanish Television is manipulating things because we said the aggression was directed at the King and not at Sánchez.”

The manipulated clip trimmed the original piece, presenting a distorted version:

“If you watch the full news video, it tells you how the King withstood the moment […] and gives you the full story—that all three, the King, Mazón, and Sánchez, were hit by the mud.”

This out-of-context fragment suggested that TVE promoted a narrative of aggression only against the King, downplaying the hostility towards Sánchez.

The online attacks escalated quickly:

RTVE’s Deployment Begins

RTVE had already been covering the disaster for several days when, at 4:30 AM on November 5, a second team led by Ferran Garrido entered Paiporta, one of the hardest-hit areas. The town, south of Valencia, had been severely flooded by an overflowing ravine.

“We managed to enter Paiporta at 4:30 in the morning,” recalls Garrido.

His team replaced RTVE’s first crew, which had been there in the initial aftermath. They entered from the town’s southern part:

“We entered the south of Paiporta, south of the ravine […] it’s a well-known area because there’s one of the largest supermarkets there. And the first thing I saw was the parking lot completely full of cars, piled one over another.”

From there, they headed to the local health center:

“The level of destruction we found was apocalyptic.”

An Initially Warm Welcome

Despite the chaos and pain, locals welcomed the team warmly. Garrido remembers a poignant moment:

“I clearly remember a man looking for his father. He told us, ‘You’re the first help we’ve seen arrive.’”

Days later, the same man told Garrido that they had found his father’s body in the garage. He had tried to save him, but was swept away by the water.

At the time, institutional aid had not yet reached many neighbourhoods. Garrido noted the understandable frustration among victims:

“We had that same feeling—we arrived in places where there was no one.”

Over time, that frustration sometimes morphed into hostility toward the press. Garrido emphasized the difference between empathy and justification:

“It’s one thing to share in the people’s anger […] and another to justify what happened to us afterward.”

First Harassment Episode

On Friday, November 8, nearly ten days into the DANA, Garrido’s team traveled to Algemesí, just 8 km from his hometown:

“It’s my region—I have a special bond with it. My own town is one of those affected.”

They parked in the market square, an accessible yet ravaged area, and began exploring the urban centre on foot. That’s when Garrido noticed a man who appeared in various locations.

Initially he was helping volunteers clean up. Later, Garrido saw him again in front of the local library with a different group. The man stood out due to his build:

“A big, tall guy—he stood out. […] I thought, ‘Wow, he’s really making the rounds.’ I didn’t think much of it.”

That morning, Garrido appeared live several times for TVE’s morning news and Canal 24 Horas. In the afternoon, they prepared a live segment for Telediario’s early evening edition. They planned to showcase a street that reflected the full devastation of Algemesí.

Just as they began broadcasting, the same man reappeared—this time from behind a pile of debris:

“He lunged at us […] I moved right to adjust the camera, and he noticed. Then he lunged at the camera, started shouting insults.”

🔗 https://www.rtve.es/play/videos/telediario-1/08-11-24/16322559/ (MIN 12:37)

The newsrooms in Madrid cut the feed immediately, but Garrido wanted to keep broadcasting:

“If a citizen is shouting, people need to see that. Because if we hide the attacks, we stop existing as victims.”

The footage was later edited and spread online under headlines like “TVE manipulates” or “TVE censors citizens.” Garrido denounced the distortion:

“I’m just doing my job […] and now look: ‘TVE censors citizens.’ Unreal.”

The video circulated on social media platform X, where users began encouraging more attacks against public television journalists:

“A DANA victim BOYCOTTS TVE live: ‘You bastards, people are dying and you do nothing.’”

Later, Garrido confronted the man, who had no connection to the volunteers. When asked why he behaved that way, he responded:

“TVE is manipulating, you’re lying.”

Garrido replied:

“You can’t know what we’re saying—you didn’t even listen.”

One of the volunteers clarified that the man was a stranger, not from town, and the encounter ended with the man fleeing while shouting:

“Typical bully behavior—runs away yelling as if he were the one being attacked.”

This was a deliberate attack, Garrido believes. The man’s recurring presence and the later online use of the footage pointed to preplanned intent.

Second Attack – Massanassa, November 9: A Broadcast Under Siege

The second documented incident occurred on Saturday, November 9, in Massanassa, south of Valencia. Unlike the first, this episode was gradual and increasingly tense, culminating in National Police intervention.

The day began without incident:

“We worked in Ground Zero […] did everything, no problems.”

At around 4 PM, they were instructed by Madrid to prepare a live segment focusing on the isolation felt by locals:

“My editor told me: we want to talk about the loneliness of the neighbours.”

They found a street partially cleared thanks to community effort. A resident said:

“It’s been intense—we had to do everything ourselves.”

Around the corner, the situation changed dramatically:

“A street with no light, mud everywhere, furniture, debris—it looked like a jungle.”

The segment showcased this contrast between recovery and collapse:

“This street was cleared by neighbours. But this isn’t the norm. Look to the right […] no lights […] this is the loneliness of the nights.”

But once they turned on the spotlight, things escalated. From a balcony, yelling and insults erupted:

“Wild screams, insults—they said everything.”

“He asked why we were filming the clean streets […] I said, ‘This is where I started—because there’s light.’”

A crowd of around 20 people formed—most unknown to the team, suggesting some level of coordination:

“Suddenly it felt like a staged event […] these people weren’t here a minute ago.”

Despite the hostility, Madrid greenlit the live feed. Garrido incorporated the tension:

“As you can see, there’s a lot of anger among the neighbours.”

“They’ve cleaned their street, but look just around the corner—mud, destruction, abandonment […] this is loneliness.”

The episode ended with National Police arriving:

“They waited for me to finish, then asked us to pack up and leave.”

Garrido admits things could have turned violent:

“It could’ve gone badly—we endured shouts, insults, they threw stuff at us. It lasted about 15 minutes.”

The incident went viral on platforms like X, with some videos racking up nearly two million views. Others encouraged further aggression:

The Actors and Channels of Dissemination

Among the various accounts that shared attacks on reporters covering the devastation caused by the DANA, we identified the following profiles:

- Influencers presenting themselves as legitimate journalists

- “Patriotic” influencers

- Telegram channels that share content linked to conspiracy theories or far-right ideologies

It is important to note that in this case study, no evidence was found of coordination between these actors to discredit the work of journalists or media outlets. As in other cases analyzed by the IPI-led Observatory of Disinformation Narratives Against the Media, these actors are connected through networks that share similar ideologies but often operate as “lone wolves”—not directly tied to political parties or extremist movements, but instead serving content to their own audiences, which in some cases reach hundreds of thousands of followers.

It is also important to highlight that sustained disinformation campaigns in Spain aimed at eroding trust in the media have created fertile ground for the proliferation of such actors and the spread of derogatory and intimidating content against journalists—especially those working for public media, or private outlets with a progressive editorial stance.

Next, we analyze the profiles of these actors, focusing specifically on the content they share and the networks in which they operate to better understand the ideological ecosystem they belong to. For this, we used two types of specialized software for crawling and network analysis: Gerulata Technologies and Open Measures. Both are widely used by researchers, academics, and communication professionals.

In total, 369 messages were analyzed between October 29, 2024 (the first day of the floods) and December 31, 2024, across three platforms: X (formerly Twitter), Telegram, and web URLs. The same Boolean search prompt was used in both tools:

“rtve OR tve AND dana.”

- Total messages analyzed: 369

- Messages discrediting journalism, RTVE or the press: 103

- Cumulative audience:

- Total views: 14,708,426

- Total likes: 662,908

Total shares: 43,282 - Average engagement per message (likes + shares): approx. 6,856

Influencers presenting themselves as legitimate journalists and “patriotic” activists

Three X accounts were identified disseminating anti-RTVE posts in their channels. With 1.5 million views, they were major vehicles for spreading content discrediting journalists’ work.

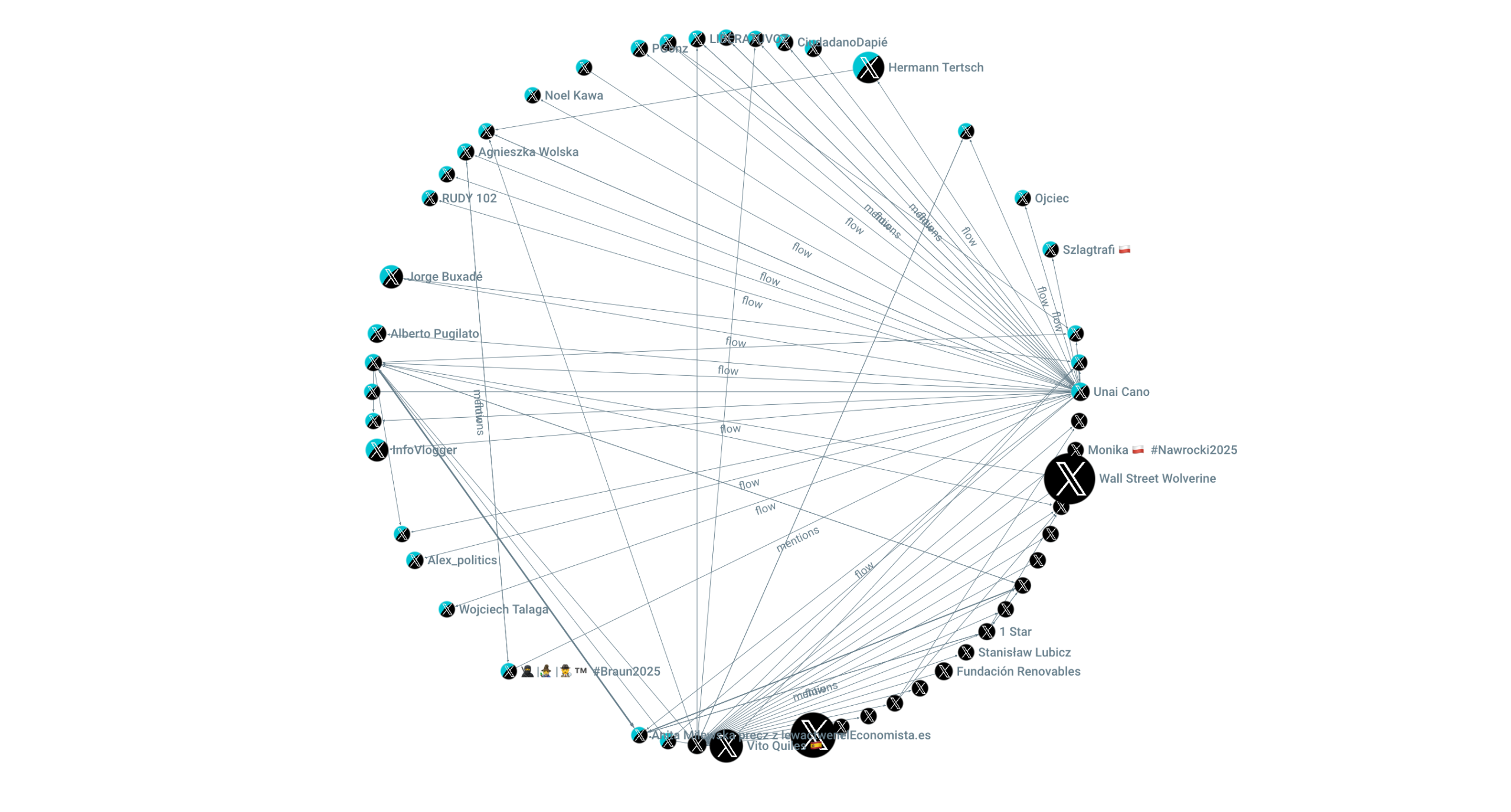

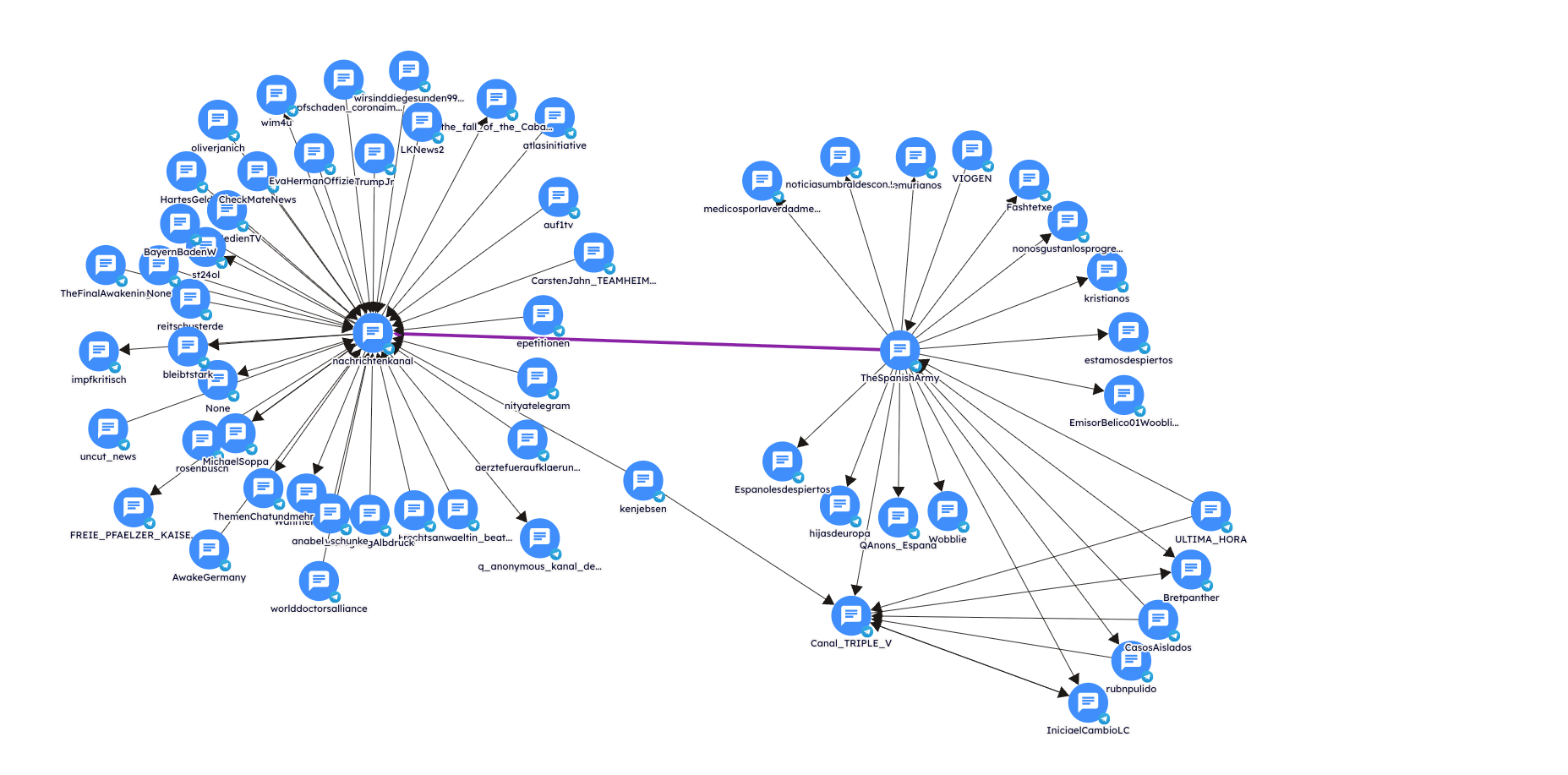

This Social Network Analysis (SNA) shows a dense, well-connected network of ideologically aligned actors. Within it, conspiratorial narratives and attacks on RTVE during the DANA coverage were amplified by pseudo-journalistic influencers, far-right digital activists, and even international disinformation accounts.

Each node represents an X account. The node size reflects its centrality in the network (number of mentions or interactions). Lines represent relationships: amplification (“flow”), direct mentions, or interactions (e.g., replies, retweets).

Among the most central and influential nodes are Wall Street Wolverine, Unai Cano, and Vito Quiles. These accounts function as key amplifiers—receiving and redistributing content or serving as reference points for conspiratorial and anti-establishment narratives.

On the right side of the graphic, other ideologically far-right or conspiratorial figures appear, such as Herman Terstch (an Member of European Parliament known for persistent attacks on public media and for supporting media-manipulation theories) and infoVlogger, a geopolitical and conspiratorial influencer known for disseminating diminishing content against traditional outlets.

A typical amplification mechanism works like this: A key node (e.g., Wall Street Wolverine or Unai Cano) posts or shares out-of-context content. Accounts like Vito Quiles amplify it, adding a narrative spin (e.g., “RTVE hides this”). Political influencers cite it, inflating the message’s reach and viral potential.

This ecosystem requires no explicit coordination. Shared ideology and ready-made visual material act as accelerators.

Telegram channels sharing conspiratorial or far-right content

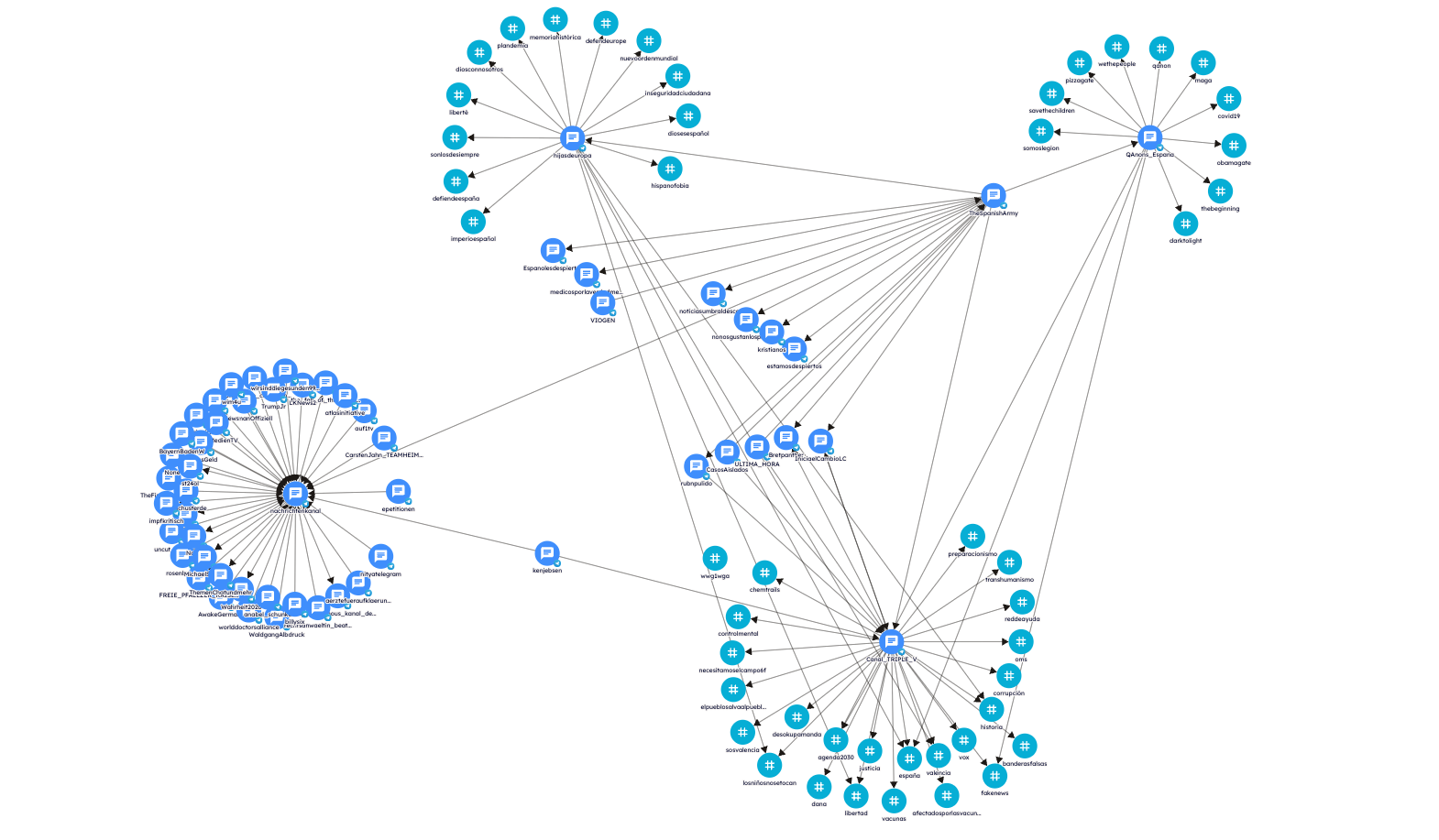

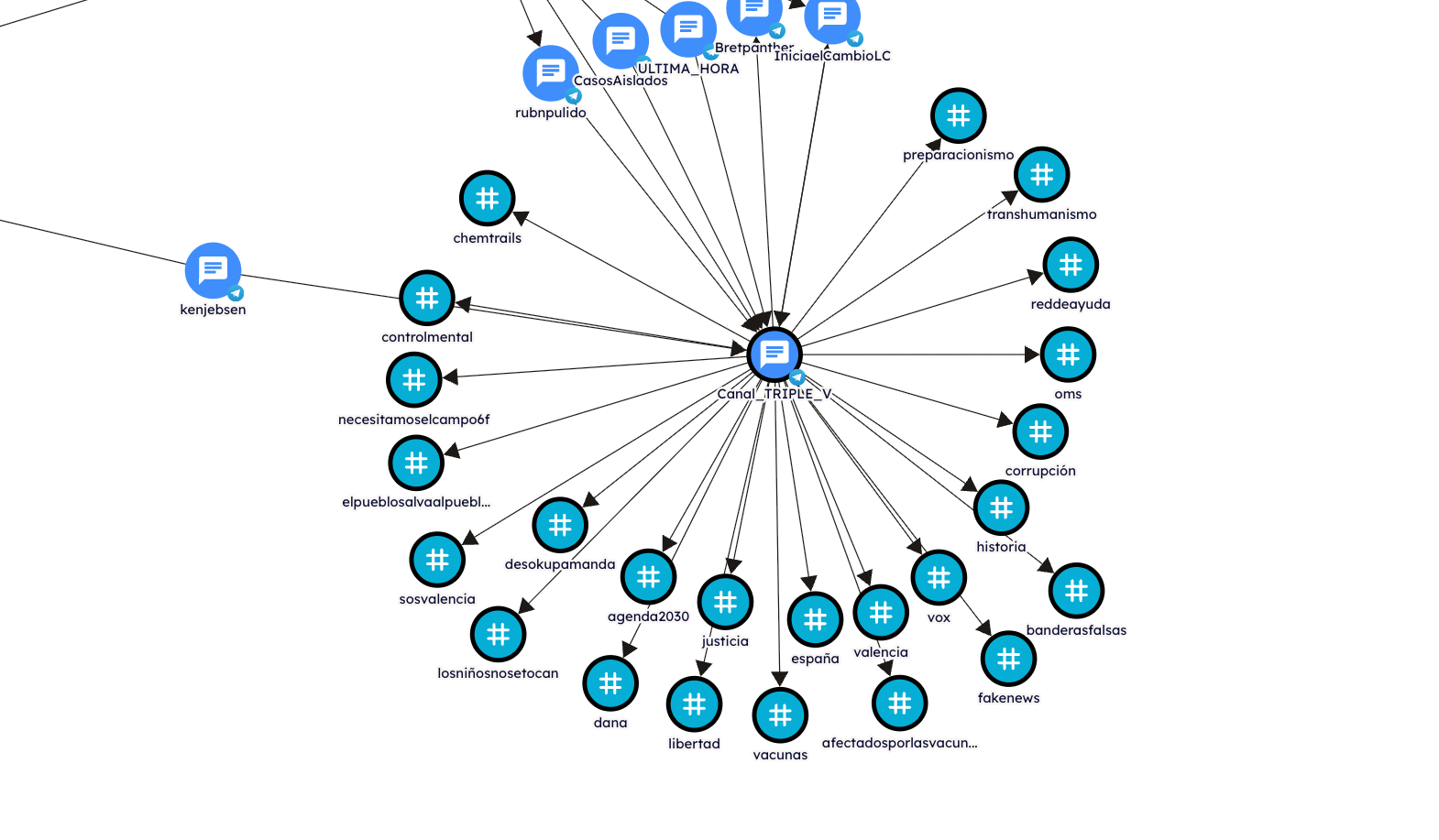

This set of graphics shows an analysis of Telegram networks that spread content critical of RTVE during DANA coverage, especially Canal Triple V and The Spanish Army (TSA). Below is a structural and thematic breakdown of this disinformation ecosystem and its ties to conspiratorial and far-right ideologies.

Canal Triple V is a central node distributing intersecting conspiratorial content. It uses the natural disaster as a pretext to introduce themes such as:

- Criticism of RTVE and public media as part of a “manipulative system”

- Classic conspiracy themes: forced vaccination, mind control, collapse of the state, and theories about the “Great Reset”

Associated hashtags:

#agenda2030, #banderasfalsas, #controlmental, #libertad, #elpubleosalvaalpueblo, #sosvalencia, #dana, #afectadosporlasvacunas, #oms, #fakenews, #transhumanismo

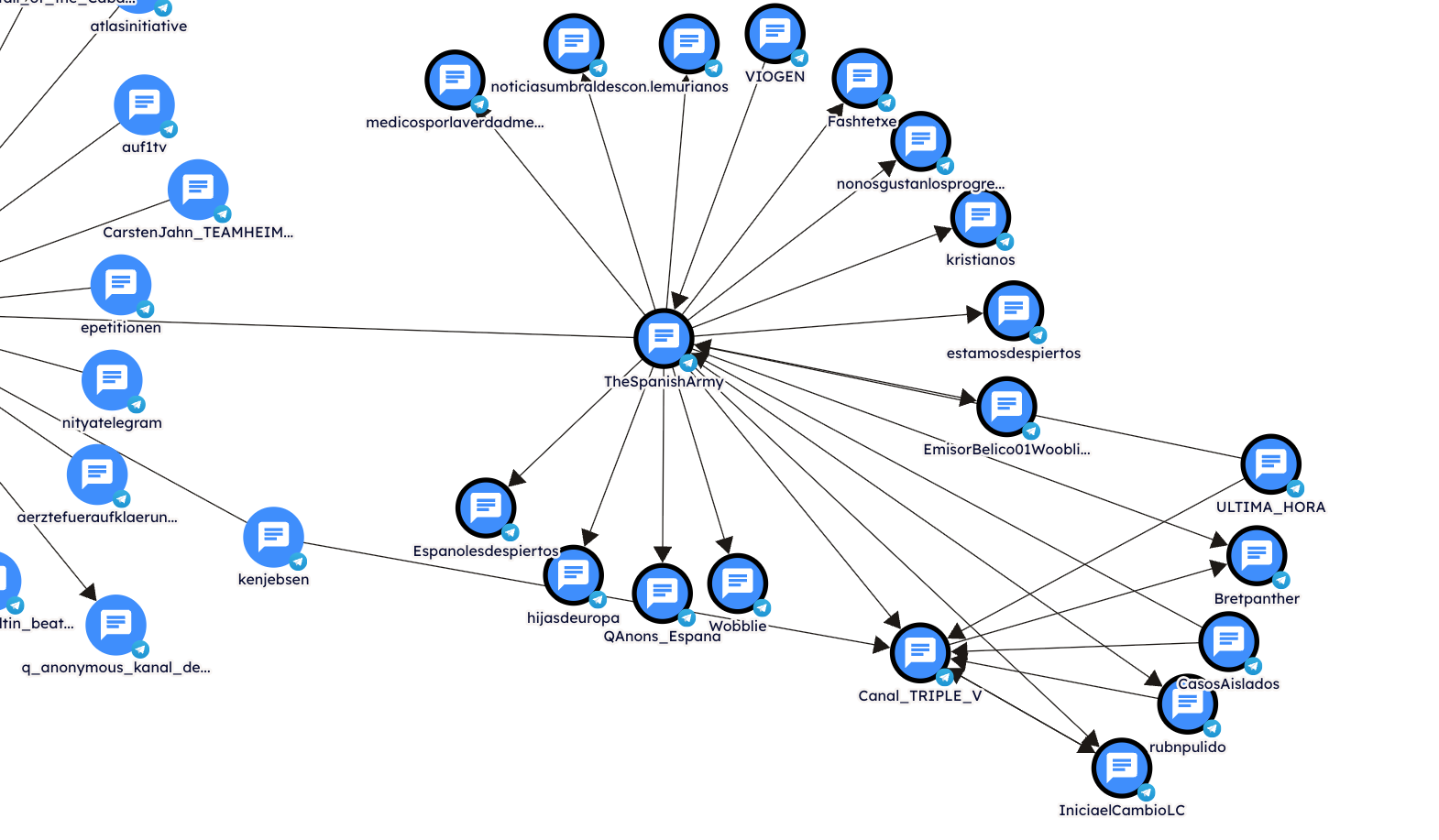

The Spanish Army (TSA) serves as a repackager and distributor of conspiratorial content in multiple languages. It shares:

- Protest clips targeting institutions (RTVE, government, EU)

- QAnon and New World Order (NWO) rhetoric

- Highly emotional, viral content: rescues, protests, “silenced” interventions

Associated hashtags:

#plandemia, #saveeurope, #despierta, #covid1984, #thebeginning, #darktoight, #newworldorder

Key connections: TSA has notable links with German-speaking channels like “nachrichtenkanal” and “impfkritisch,” showing a transnational disinformation bridge.

Narratives against RTVE

1. RTVE as an ideological arm of the State

RTVE (Spain’s public broadcaster) is portrayed in these posts as government propaganda—no longer a public service but a tool to push a political agenda, often tied to leftist or ruling party ideology. The criticism goes beyond content, targeting RTVE’s institutional role in shaping public opinion.

Example (Wall Street Wolverine):

🔗 https://x.com/wallstwolverine/status/1853416086722453747

“This just happened live on RTVE:”

(Attached to a supposedly ideological clip provoking outrage)

Example (TSA Noticias):

🌩 ➡️ “TVE, now completely controlled by PSOE, brings on an ‘expert in responsibility distribution’ to say the DANA is entirely Mazón’s fault.”

2. Hiding the truth and media censorship

RTVE is then accused of covering up events during the DANA—especially those damaging to the government or contradicting the official narrative. This framing suggests RTVE selects what to show for political motives, and even demonizes dissent by labeling citizens or creators as “radicals” or “extremists.”

Example:

🔗 https://x.com/Capitana_espana/status/1854216504260149365“They’re trying to delete this from RTVE’s archives, but we won’t let them. What’s up?”

Example:

🔗 https://x.com/YoRevoltijo/status/1855361307936989358“While RTVE talks about climate change, this is really the result of political neglect. But they won’t say that.”

Example (Pablo Haro Urquízar quoting Jano García):

“Remember the faces of the bastards who come after you if you’re not left-wing. They’re at RTVE.”

3. Disconnect from citizens’ reality

A subtler narrative claims that RTVE is more focused on defending a political agenda than reporting real events. In a disaster like the DANA, this becomes especially powerful—accusing the public broadcaster of bias or using tragedy to reinforce its editorial stance.

Example:

🔗 https://x.com/AdaaLovelacee/status/1854919938877612464

Example:

“A TVE cameraman curses out a DANA victim from Valencia.”

🔗 https://x.com/MediterraneoDGT/status/1854831341415669782This false claim was debunked by RTVE: it was not a TVE cameraman.

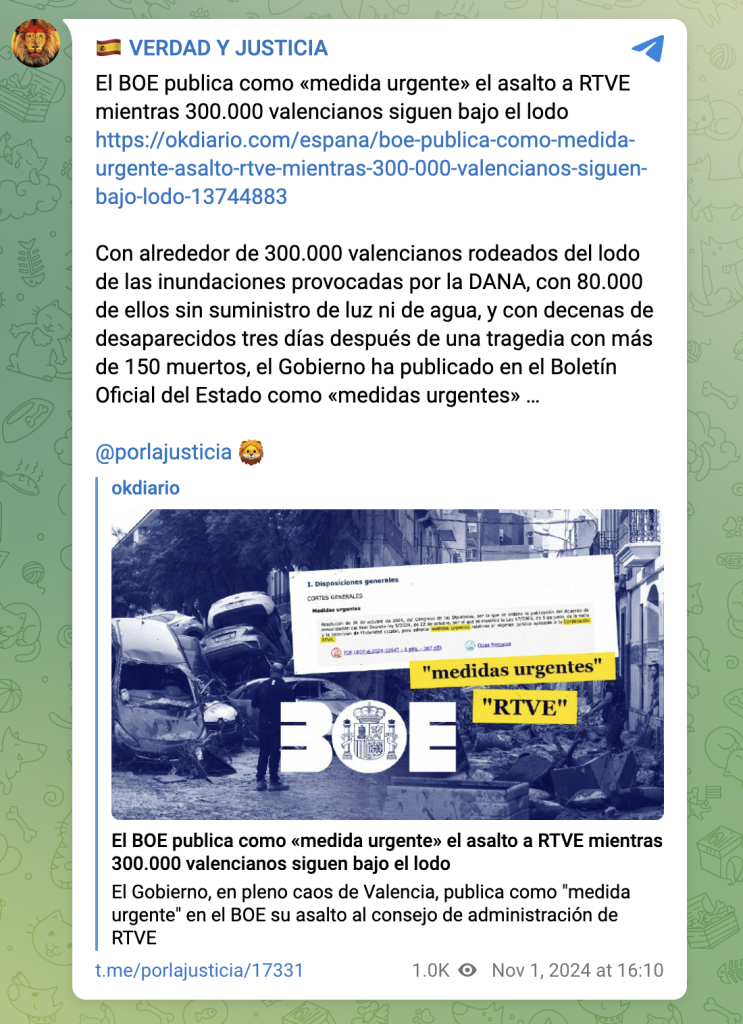

🔗 https://www.rtve.es/noticias/20241108/falso-camara-tve-no-insulta-vecino-paiporta/16322606.shtmlExample (Telegram):

🔗 https://t.me/porlajusticia/17331

Conclusions

The attacks against RTVE journalists during the deadly floods should not be seen as isolated events, but rather as symptoms of Spain’s deeply polarized media and social ecosystem. The convergence of three factors—collective grief, institutional miscoordination, and organized disinformation—created a uniquely hostile environment for field reporters.

The case of Ferran Garrido illustrates how a journalist shifted from being a narrator of tragedy to a target of orchestrated narratives: from live disruptions to manipulated videos going viral, fueling the image of RTVE as manipulative, censoring, and government-serving.

Telegram channels played a central role in disinformation dissemination and amplification. Analysis of hashtags and connections reveals the interweaving of conspiracy theories (mind control, WHO, vaccines), far-right ideology (anti-Agenda 2030, anti-system, ultranationalism), and systematic attacks on RTVE. Their messaging is emotional, binary, and exclusionary—framing the narrative as a fight between “the people” and “corrupt media.”

The increasing role of pseudo-journalistic influencers, ultranationalist and conspiracy activists, that have grown in number partly due to the social polarisation in a strenuous political environment, shows how the drive for online viral content has replaced journalistic rigour. These actors don’t need evidence or coordination to undermine public trust in fact-based journalism and the media—ideological alignment and viral reach are enough.

This case study confirms the urgent need to strengthen public journalism and fact-checking, both essential sources of reliable information in emergency situations, improve citizens’ media literacy, and establish institutional responses to online harassment and disinformation campaigns targeting the media. It also underlines the need to hold platforms accountable for their slow response (if any) in the face of rapid proliferation of falsehoods in their feeds that could potentially endanger journalists’ safety working on the field, especially as the climate and environmental crisis deepens, increasing the likelihood of natural disasters.

Though Europe equipped itself with a set of regulations in the Digital Services Act (DSA) to hold platforms accountable for, among other things, the spread of disinformation, authorities did not enforce them during this emergency crisis in Valencia, despite containing specific provisions to address this issue in the case of such events. These provisions allow European authorities to urge platforms to implement specific, relevant, and proportionate measures, such as providing warning messages that lead to reliable and official sources when users search in social media for information linked to natural disasters. However, according to research conducted by Maldita, the EU did not enforce these provisions during the deadly floods in Valencia.

Without structural action, journalists will remain scapegoats in crises where access to fact-based information might be a matter of life or death.